Why Do We Lose the Desire to Follow the Quest-ion?

“The important thing is not to stop questioning… Never lose a holy curiosity.” – Albert Einstein

Probably the two things we associate most with curiosity are children and questioning. We remember childhood as a time of openness and inquisitiveness, we observe children approaching even the most mundane things with a sense of awe and wonder, and as parents we weather the barrages of questions that follow. They have a fervent and intrinsic desire to know and learn. Renowned child psychologist Jean Piaget wrote that curiosity is “the urge to explain the unexpected” and for infants almost everything is unexpected.

But what happens to us? Once upon a time we were all children, with that wonder in the world around us, that intrinsic desire to learn and know, and that willingness to follow any question about anything that stirred our fascination. Is the main thing that separates children from adults joy in discovery, in the desire to know, in curiosity?

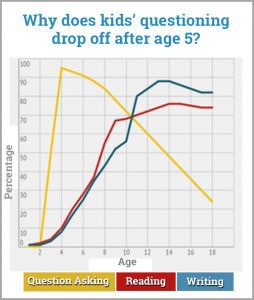

Numerous studies have demonstrated the precipitous decline in ‘questioning’ between the ages of 4 when children will ask as many as 300 questions in a day (1), and their entry into middle school when they’ve almost stopped asking questions at all. Part of the answer lies in natural neural development. From infancy to early childhood there is a cosmic explosion of billions of neural pathways and networks wiring themselves together in hyper-complex adaptive systems; it’s all growth growth growth. But then this process slows down and enters into a new era of trimming back, called ‘synaptic pruning’. However, ‘synaptic pruning’ does not adequately explain what Warren Berger, the author of ‘A More Beautiful Question’, described as the drop of questioning off a cliff.

So, what else happens at that age?

First off, as comedian Louis CK demonstrates in this brilliant scene from ‘Lucky Louie’, answering the barrage of ‘why’s’ that can come at any moment from a curious 4 or 5 year old can get pretty sublime. It’s also pretty exhausting, and overly busy parents, struggling to conform to their own productivity driven milieus, just can’t ‘go there’.

But beyond weary parents, a great many researchers have demonstrated that this decline is due in very large part to the systems that children enter into when they are old enough to attend school. The education system is not designed to cultivate curiosity. If anything, in fact, it’s designed to discourage questioning. Children are rewarded for knowing answers, not for asking questions, and the goal of education is not to learn to explore and learn, but to ‘get the right answer’ (2). As Developmental Psychologist and Curiosity researcher Susan Engel puts it, “Curiosity that is ubiquitous in toddlers is hard to find at all in elementary school”.

Current education systems, worldwide, grew out of the industrial revolution and are designed to produce human resources that will efficiently and successfully find work and ‘be productive’ in an industrialised environment. “Our education system has mined our minds in the way that we strip-mine the earth: for a particular commodity.” says Sir Ken Robinson, in his renowned TED talk ‘Do Schools Kill Creativity?’. That ‘commodity’ would be a relatively docile, malleable and compliant person, highly literate in abstract mathematics and written English. That is, a manageable person well adapted to the work force of an industrial culture where managers want answers to bottom-line problems – fast. But let’s face it, curiosity, by nature, isn’t docile, malleable or compliant so it’s no surprise that curiosity has it’s wings clipped in school. As Einstein put it so very succinctly, “It’s a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.” I propose that for many, it doesn’t.

Children born today will be leaving high school in the mid-2030s. Who dares to predict the nature of the culture into which these children will be emerging from school? Few today dare to predict what the world will look like in five years, let alone twenty. What we may be able to say with some certainty is that they won’t be emerging into an industrial culture anything like the one for which the formal education system was designed (3). We are faced with a shocking degree of uncertainty and unpredictability; a great unknown.

Children born today will be leaving high school in the mid-2030s. Who dares to predict the nature of the culture into which these children will be emerging from school? Few today dare to predict what the world will look like in five years, let alone twenty. What we may be able to say with some certainty is that they won’t be emerging into an industrial culture anything like the one for which the formal education system was designed (3). We are faced with a shocking degree of uncertainty and unpredictability; a great unknown.

And what is the most intelligent attitude towards the unknown? The very aptitude that is determinedly clipped in the process currently called education and ‘literacy’: curiosity. Curiosity, the intrinsic desire to know, is *the* most essential character impulse in the face of the unknown. Intelligence itself follows curiosity which, like an impetuous scout, dares into the dark to cast light and map paths and possibilities. Success based on the necessity to ‘have all the right answers’ is antithetical to the ‘quest’ of curiosity. How can you possibly have the right answers when you’re entering the unknown? It’s an absurd notion.

The ‘questing’ heroes of the chivalric romances – Gawain, Lancelot, Galahad – were called ‘knights-errant’. To ‘err’ meant ‘to be wandering in search of something’. The linguistic migration of the word ‘errant’ from ‘a noble quest’ to the ‘incorrectness’, ‘deviation’ and just plain ‘wrongness’ of ‘error’ is a powerful indicator of the cultural stigma against ‘quest-ioning’ and curiosity.

Curiosity is following a quest-ion.

Curiosity is a dynamic of ongoing inquiry.

Curiosity is a virtuous cycle of recurring, adaptive questioning.

Curiosity is also the evolutionary strategy by which humanity became the dominant species on the planet earth. Given the the extraordinarily disruptive uncertainty of our global future, curiosity may be the aptitude that enables humans to continue to evolve (4). Surely this is a compelling reason to integrate the cultivation of curiosity into educational curriculums and workplace cultures everywhere.

(1) According to Paul Harris, a Harvard child psychologist and author, research shows that a child asks about 40,000 questions between the ages of two and five.

(2) “In school, we’re rewarded for having the answer, not for asking a good question.” – Richard Saul Wurman, founder of TEDTalks.

(3) The World Economic Forum claims that we are in a ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’. I would argue that it’s not an ‘industrial’ revolution at all; maybe it’s a biological revolution, or a digital revolution, or a virtual revolution. But ‘industry’, as the great economic engine which upholds nations, is in it’s final throes…

(4) Hopefully to evolve beyond ‘dominance’ towards symbiosis and sustainability.