When Values Meet Addictions

Why aspirational values differ, sometimes drastically, from behavioural values

The theme of Toronto Change Days 2019 was ‘Living Values’, and through the course of the ‘unconference/celebration’ of change, participants used the HowSpace conference app to enter their top five values four times: before the conference started, and then in increments throughout the weekend. Word Clouds created from the input of all the participants gave a picture of how our values shifted throughout the experience.

The values which showed up in the Word Clouds were, possibly, a little predictable: Integrity, Compassion, Curiosity, Honesty, etc. Noble value aspirations which we aspire to and which we see commonly in organisational value statements. But, as the weekend wore on, I began to feel there was a disconnect.

The Cambridge dictionary gives a single definition of values which is in keeping with the value proclamations at Toronto Change Days: “the principles that help you to decide what is right and wrong, and how to act in various situations”. Dictionary.com has a couple of alternate definitions which complicate the matter: “the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something.”, or “a person’s principles or standards of behavior; one’s judgment of what is important in life.” One definition is that values are what we see as ethically or morally noble or correct, another definition is that values are what is important or useful. These two definitions have an alignment problem.

No organisation anywhere, including every fossil fuel company (1), has ever proclaimed that they value global warming. But the very planet we dwell in is exponentially heating up as a result of greenhouse gases created by human activity imperiling the very existence of future generations. Researchers, governments, and even fossil fuel companies have known this for decades but, despite decades of value proclamations about sustainability, our climate changes precipitously quickly.

No person anywhere has ever proclaimed that they valued ending up on the street as a result of substance abuse. But every day in my neighborhood in Parkdale, Toronto, I see people who have valued addictive substances above anything else, and as a result are homeless and destitute.

So, there can be a very significant disconnect between ‘proclaimed’ values, and ‘actual’ or ‘behavioural’ values.

Dutch former ad exec and co-founder of ‘Church of Change’ Stephan Ummelen ran a workshop during the conference entitled “79% of Values are Bullshit”. With a small team of researchers he assessed the value statements of organisations compared to how their staff evaluated how these same organisations lived up to those values. The results of his research were that organisational value statements were precisely 79% bullshit. I believe that the same can be said of our own personal value statements. While we may express that we value Integrity, Compassion, Curiosity, and Honesty, in the messy grist of every day we behave in ways that undermine those value proclamations.

We actually value other things.

Why is that?

The problem of this discrepancy isn’t anything new. The ancient Greeks called it ‘akrasia’; “a lack of self-control or the state of acting against one’s better judgment” and Plato in the dialogue ‘Protagoras’ describes a debate between Socrates and Protagoras which elucidates their opinions on this. 500 or so years later Christianity’s most zealous early evangelist the Apostle Paul proclaimed, in a kind of despair, “For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing.” (Romans 7:15, NIV).

The problem of this discrepancy isn’t anything new. The ancient Greeks called it ‘akrasia’; “a lack of self-control or the state of acting against one’s better judgment” and Plato in the dialogue ‘Protagoras’ describes a debate between Socrates and Protagoras which elucidates their opinions on this. 500 or so years later Christianity’s most zealous early evangelist the Apostle Paul proclaimed, in a kind of despair, “For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing.” (Romans 7:15, NIV).

Why do we ‘not do the good that we want to do’?

Why do we profess and aspire to one set of values and yet in our behaviour, day in and day out, follow another.

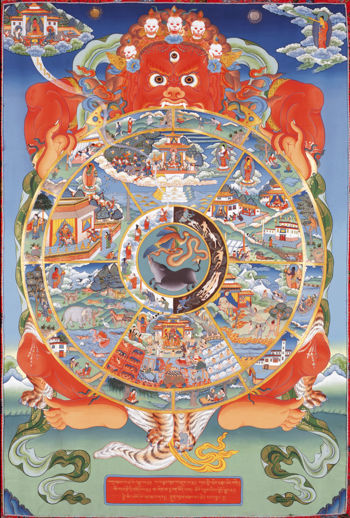

About simultaneous with Socrates, and 500 or so years before St Paul, Siddhartha Gautama, aka ‘The Buddha’, had an alternate answer to the question of ‘akrasia’. Following a lengthy experiment with radical asceticism he arrived at a description of humanbehaviour which, to my mind, still has great relevance today. His ‘Second Noble Truth’ (the First Noble Truth being that ‘All Life is Suffering” – a little harsh but most of us can relate to some degree) is that the reason for suffering is that we’re attached to, or crave, things that don’t last (they’re ‘transient’), and our dependency on those things causes us to suffer. Our attachment to temporal things results in our being caught into a cyclical world which he called ‘Samsara’ (the Buddha described the craving as a ‘flame’ and ‘Nirvana’, the ultimate goal of his philosophy, as the extinguishing of that flame). Samsara, in the traditional sense, is the birth-death-rebirth cycle. If we haven’t resolved our attachment to ‘things’ in this lifetime, we’re born again to try and figure it out again (better luck next life). But Samsara also refers to the ‘cycles’ we engage in everyday: the behavioural loops, the dramas we get hooked into, despite our most noble aspirations, day after day, night after night.

In contemporary-speak that’s called ‘addiction’. Gabor Mate – one of the world’s foremost addiction theorists, a doctor who spent decades working on the front-line of substance abuse on Vancouver’s East Side – defines addiction as “…any behavior that a person craves, finds temporary relief or pleasure in but suffers negative consequences as a result of, and yet has difficulty giving up.” Sounds a lot like the reason for ‘akrasia’. Ann Wilson Schaeff, who wrote ‘When Society Becomes an Addict’ and ‘The Addictive Organisation’, takes it a little further. Schaeff writes that addiction is “any substance or process that begins to have a control over us in such a way that we must be dishonest with ourselves or others about it… If there is something that we are not willing to give up in order to make our lives fuller and more healthy, it probably can be classified as an addiction.” There are substance addictions, which are pretty easy to recognise, but there are also process addictions: “process addictions refer to a series of activities or interactions which ‘hook’ a person, or on which a person becomes dependent.” She includes in these addictions such things as work, money, religion, relationships and even certain types of thinking. According to Schaeff, most societies actively foster addictions.

My proposition is that the span between aspirational values, and behavioural values, is addiction.

I’m an addict…

Fortunately I’m not alone.

I propose that we’re all addicts, and that the organisations we work in, and the cultures we live in, are largely founded on behaviours that encourage and/or reward addiction.

I had a revelation many years ago about how addiction was affecting my values. I was driving into a small town in Nova Scotia with my partner and child and I valued first and foremost my child and my partner, and also learning, and the sense of discovery of this small town, it’s history and the special fascinating places that could be discovered. But I was also addicted to alcohol so, as we drove into the town I was preoccupied with where the beer store was (in my minds eye the orange sign of the Beer Store was lit up in my head like a church steeple) and how I could acquire enough alcohol to get me through the night without anyone really knowing about it (which worked against other professed values; honesty and transparency). My need to satisfy my addiction – my behavioural value – worked against my professed values. Simply stated, as we drove into town I was valuing the location of the beer store, and how I might finesse getting in and out of there without anyone really knowing what I was up to, more than I was valuing finding and exploring cool historical sights, or even making sure my partner and child were well accommodated and genuinely happy. I was Jonesing (slang for the somatic experience of anxiety when you’re not getting your ‘fix’), and that experience of ‘Jonesing’ was compelling my decision making. It was then that I first realised that my addiction, which was determining my behavioural value system, was a tyrant.

In the 2006 State of the Union Address George Bush proclaimed that “America is addicted to oil”. Bush went on to say “The best way to break this addiction is through technology. Since 2001 we have spent nearly 10 billion dollars to provide more reliable and more cleaner technology sources. And we are on the threshold of incredible advances. So tonight I announce the Advance Energy Initiative. A 22% increase in clean energy research…” Yes, that was George Bush in 2006, the elected representative of the people of the United States of America, professing the aspirational values of the US government for clean energy, and freedom from the tyranny of oil. Two years later the US was invading Iraq in an illegal war which killed, depending on the report, between 150,000 and 650,000 civilians. Apparently the price of a nation, the most powerful nation on earth at the time, still addicted to oil.

Professed values differ from behavioural values.

Our real actions – personal, organisational, even national and global – are often driven by attachments which consistently undermine, and even blatantly oppose, our value statements. When our actions, at the end of the day, demonstrate habitual behaviours whose long-term consequences are illness and toxicity, it’s called addiction.

Addiction’s a tyrant.

But… we’re all addicts of one thing or another. It’s part of being human.

And addiction, once recognized and admitted to, can become a teacher.

And tyrants have been, over and over, since the beginning of organised governance, uprooted and overthrown.

- BP’s Value Statement – “We care about the safe management of the environment.”

https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/who-we-are/our-values-and-code-of-conduct.html

BP’s actual history – https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/jun/14/rise-fall-of-bp